A well-designed online classroom affords teachers many options for organizing information, facilitating interaction, providing feedback, and supporting evaluation of students’ work. For students, a well-designed online classroom facilitates all aspects of taking a course as well. This page summarizes the rationale for an online course and summarizes the work of designing an online classroom for users of any learning management system.

Overview of the Process

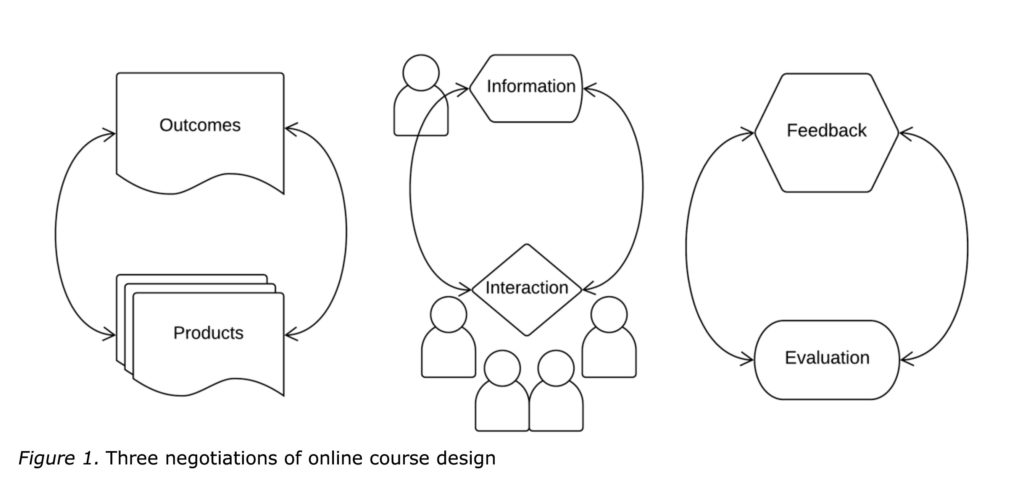

A good online course will be complete (the syllabus will include everything that it should), clear (well-organized and accessible to students), and allow for connections (between students and content and teacher and the world beyond the course). Such courses are designed through three iterative processes:

First, the outcomes and products are designed to ensure it is clear what students will learn and how they will demonstrate their learning;

Second, the information that students need to learn and interactions that will help them learn are designed;

Third, the details of how feedback will be given and how students will be evaluated are articulated.

Each step of the design process is a negotiation. Instructors and instructional designers (who have expertise in teaching, technology, and media production) discuss the best ways to leverage the capacity of the learning management system to organize the online course and structure the activities.

Outcomes and Products

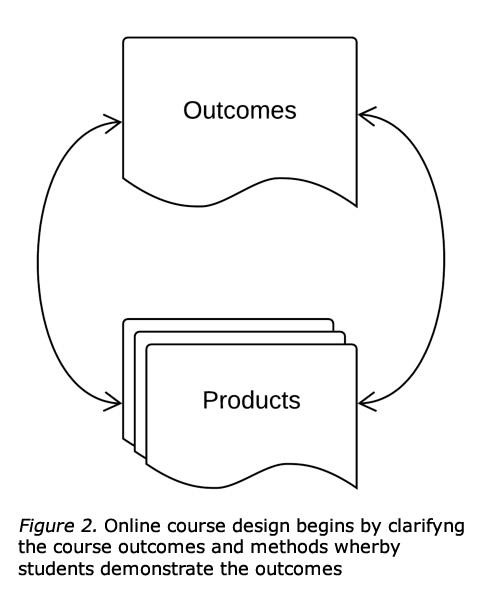

Designing an online course begins with answering the questions:

- What are students going to learn?

- How will we know they learned it?

Clear connection between what we tell students they are to learn and what we have them produce is the foundation of a good online course. In some cases, the instructor will have products in mind that are natural to their field, but that are not clearly articulated in the outcomes. In other cases, there are outcomes stated that are not reflected in the products. Clarifying these expectations becomes the foundation for the rest of the design work.

In addition to making explicit what students will learn and do in the course, beginning course design with this discussion helps the instructor and instructional designers organize the course into manageable chunks and to ensure materials are presented in a manner that facilitates successful completion of the products.

When this phase of the course design is completed, a list of outcomes or expectations will be complete and the products will be defined (although perhaps not completely detailed). Also, the placement of the products in the course will be clear so the order is sensical. Further, the path through the course is clear and both students and the instructor see increasing sophistication in the products.

Authentic Products

While tests are one way that teachers can determine students have learned what they are supposed to learn, authentic products (Herrington, Oliver, & Reeves, 2003) are associated with the good courses as well. Herrington & Herrington (2007) observed:

The tasks that students perform are arguably the most crucial aspect of the design of any learning environment. Ideally such tasks should comprise ill-defined activities that have real-world relevance, and which present complex tasks to be completed over a sustained period of time, rather than a series of shorter disconnected examples (p.70).

When students are creating products that individuals who are working in the field would recognize and the information they are creating information that is relevant to those beyond the classroom, they are likely being evaluated through authentic products.

Authentic Technology

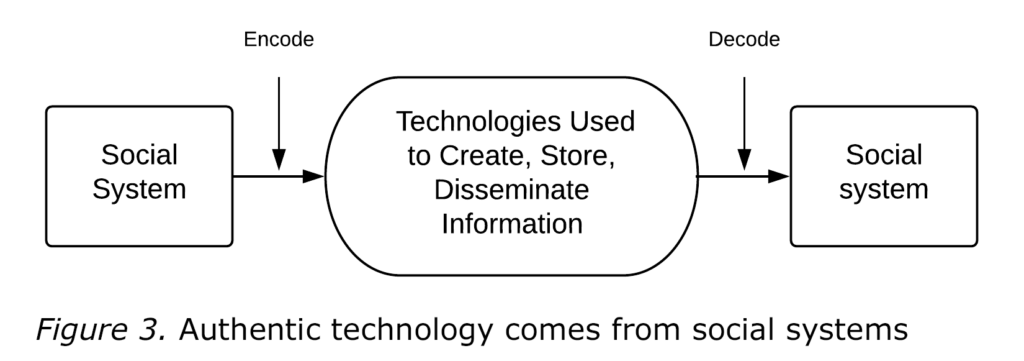

In a series of articles begun in 2007, Paul Benyon-Davies (2007, 2009a, 2009b, 2009c), a scholar from Cardiff University in the United Kingdom, used the term informatics to describe the communication and interactions that lead to and that follow from humans’ complex social groups. Benyon-Davies studied communication situations throughout human history (from ancient civilizations in South America to military operations during World War II). According to his analysis, effective communication requires individuals adopt both the language and practices of a social system, but also they must become adept at using the communication tools common in the social system.

Because most education is designed to prepare students for continued academic work and for professional positions, educators. For this reason, educators have a responsibility to give students experience using the cognitive tools in their education that they will encounter in endeavors after they leave school. For example, business students should have knowledge of the tools and features of spreadsheets, but they should also have experience creating spreadsheets that solve business problems.

Information and Interaction

Once the outcomes and products have been detailed, instructors and instructional designers turn their attention to the information that students need to accomplish the outcomes and create the products. As teaching is more than simply transferring information, this phase of course design also includes designing interactions and other activities that lead to deeper learning.

Cognitive Engagement

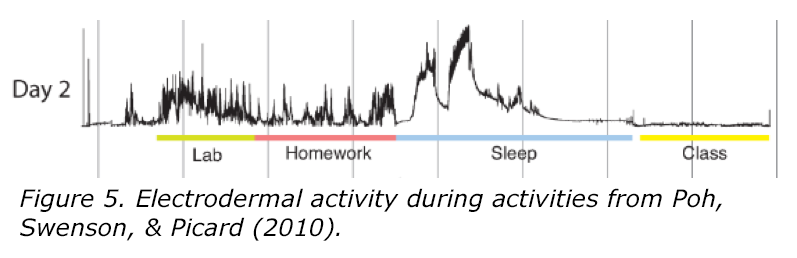

Cognitive engagement is the term used by scholars to describe the degree to which students are involved with the work of learning. The more cognitively engaged the students, the better they learn (they remember what they learn and they can more accurately apply it to new situations). Cognitive engagement begins with attention. In 2010; Poh, Swenson, and Picard found evidence of increased attention when students were engaged in active and social learning compared to time when they were in class designed to transmit information. The graph below illustrates the observed differences in electrodermal activity which is a proxy for sympathetic nervous system activity.

Accessibility: Universal Formats & ADA Compliance

Perhaps the most fundamental aspect of designing online courses is ensuring students can actually see and hear the information on the devices they use. Because students are likely to access the LMS on desktop and laptop computers, tablets, and smart phones; instructors and instructional designers post materials in universal file formats and they make sure their materials are compliant with Americans with Disabilities Act requirements for accessibility.

Universal file formats can be read by any device. Portable document format (PDF) is commonly used for documents created from word processors or presentation software. Animations that are used in a presentation file are lost when the file is exported as a PDF, but the text and images, along with hyperlinks will be displayed on any device with software widely available and installed.

As video has become a more widely-used medium for digital communication, and YouTube has come to dominate the online video market, many instructors and instructional designers have come to rely on that service for uploading their video materials. When the videos are uploaded and marked “unlisted†they can be viewed by anyone with the address of the video, but it will not appear in searches or other indexing or recommendations. The YouTube videos can be embedded in LMS pages and they will be displayed on any computer or mobile device.

The American with Disabilities Act (ADA) defines steps that government agencies must take to ensure those with disabilities can use information they create. If a course is being developed with certain grants, the funding agency will insist the materials that are created are “ADA-compliant.†This, for example, ensures screen reading software can navigate the document, alternative text describes images, closed captioning is available, and hyperlinks are labeled.

Regardless of the populations enrolled in any course and the potential need for ADA-compliant martials, it is good practice for all online instructors to create ADA-compliant materials as some students may find those features useful. For example, a student who can have an article read aloud may be able to review the material while involved in other activities. Alternatively, a student may be able to watch a video and read the captions when audio will disturb others. In both cases, online teachers and instructional designers can support expanded access to the material by following ADA guidelines.

Resources for Understanding ADA Compliance

- The Accessibility Requirement Guidelines of the Skills Commons site (the repository for materials created as part of the TAACCCT grant program) provides guidance for making accessible:

- Word documents;

- Powerpoint presentations;

- PDF files.

- The Colour Contrast Analyser (CCA) is software for Windows and Macintosh computers that “helps you determine the legibility of text and the contrast of visual elements, such as graphical controls and visual indicators.”

Discussions, Blogs, and Wikis

Discussions, Blogs, Wikis

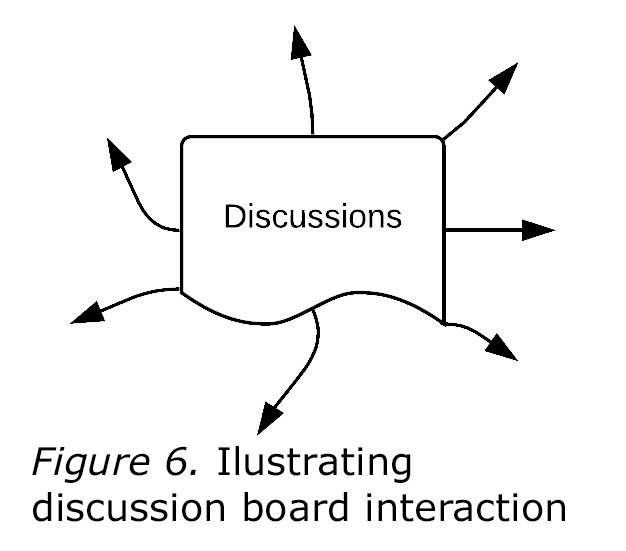

The first tool most instructors and instructional designers consider when adding interactive activities to an online course is a discussion board. In a threaded discussion, students and teachers scroll through posts (in which students have responded to a prompt from the instructor), read them, then use a reply option to post a response. Each post (or response) becomes a thread that can be opened and read. In general, online instructors and students find discussions to be divergent interactions; students extend the conversation and connect it to their experiences.

Some find threaded discussions to be a tiresome aspect of an online course. This can arise from the weak prompts that focus the interactions (see the next section), and it can also arise from the fact that discussions (even threaded discussions) are presented on a single page (or series of pages). Opening threads requires users click to open and read each thread. Navigating a discussion can become an annoying task as users either scroll and scan to find item of interest. Alternatively, they can use the search option to jump to items of interest (as long as they can identify relevant terms).

Regardless of the attention and organization used to structure and focus any discussion board, students have often had less than optimal experiences with discussion boards in online courses, so they are not enthusiastic about that part of their course and their cognitive engagement is thus limited. For all of these reasons, many instructional designers recommend either blogs or wikis as alternative tools for encouraging students to interact with each other and with course material.

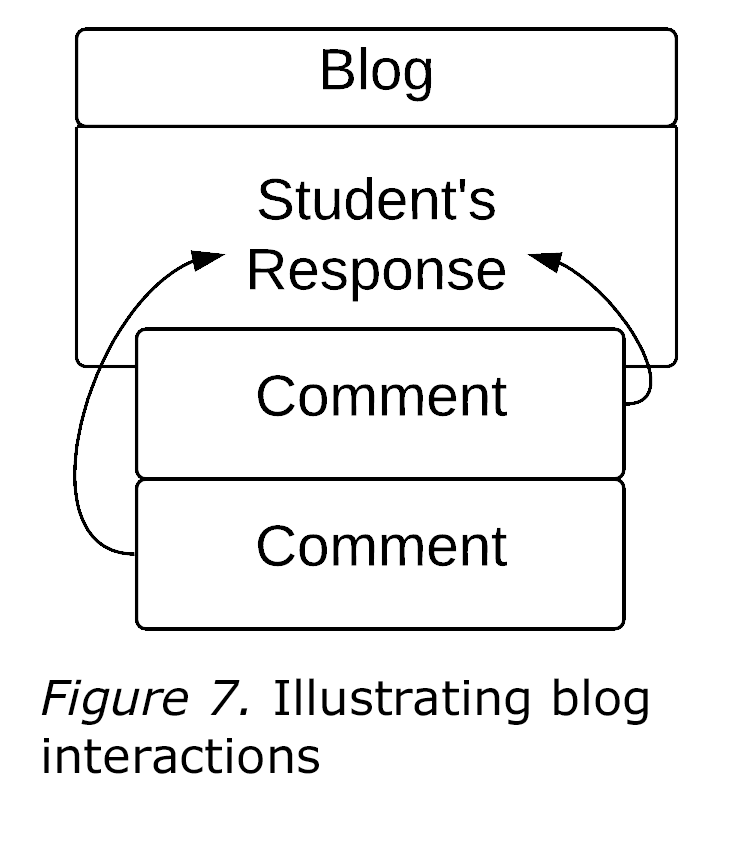

Blogs are similar to discussion boards in that interaction is based on initial posts and responses; the responses are usually called comments in blogs. As with threaded discussions, students and instructors can comment on posts or comment on comments, and those are displayed in an outline-like format. Navigating the blogs that are in an online course is different from navigating a discussion board, however. Users navigate through blogs one at a time, so they see one blog (and the comments below it), then they move on to the next blog. Many users find the focus changes in a blog compared to a discussion board. While a discussion can produce wide-ranging and divergent interaction, a blog tends to focus interaction on a single student’s post.

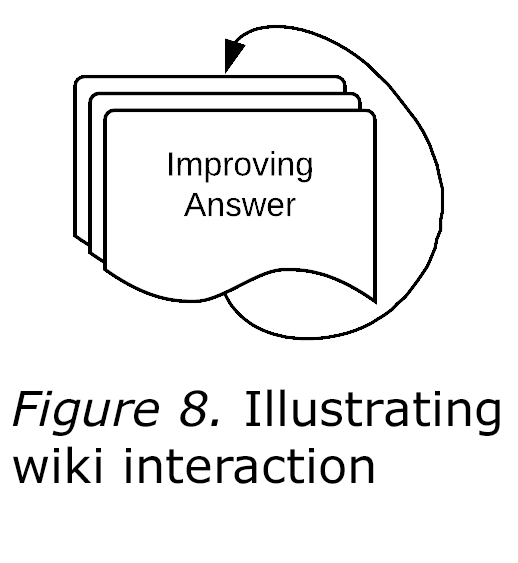

Wikis are different from either discussion board or blogs in that all participants are working on a single response. Often instructors who use wikis will pose a case study or other open-ended question or problem. As students answer the prompt or improve the answer, it emerges. Some find the wiki to be a platform they are more likely to revisit than discussion boards or blogs. Early editors are motivated to return to see how their work has been updated. Conversely, some students are reluctant to change others’ answers on a wiki. Another advantage of a wiki is the revision history that is kept. Students can use this to see how the information emerged over time, and instructors can use this to facilitate grading.

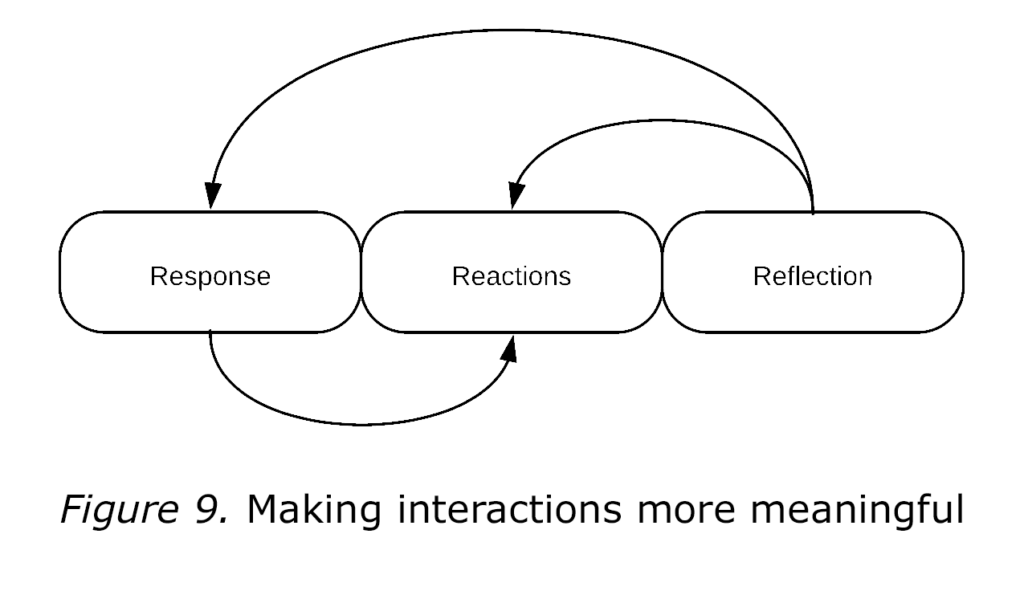

When using any of these tools to facilitate interaction among students, instructors can make it more engaging for students by structuring the approach to the discussion or blog. By approaching the interaction as three distinct phases: first, post your response, then post reaction to others, finally reflect on what you learned about the response from the reactions; instructors can make the interactions a source of new learning for students.

Prompts and Prompts

When designing discussions and other interactive elements of an online course, instructors often spend time thinking about the question that will focus each student’s initial response. In general, an assignment will:

Present an idea or an artifact (perhaps an article, video, or web site);

Students engage with the artifact, then post a reaction. In some cases, the instructor will provide a prompt to focus the reaction;

Students are then expected to respond to others’ reactions. While instructors encourage students to “do more than ‘agree'” with the responses, it is rare that instructors provide a prompt to structure students’ responses to others posts.

By defining both a prompt to scaffold the initial response and also a prompt to scaffold responses, instructors make the interaction more meaningful as the feedback is more structured and the instructor models effective professional communications through the prompts. In general, students find more structured discussions are more effective in helping them learn.

The importance of carefully structuring prompts is of particular importance because of the asynchronous nature of online interactions. Whereas a face-to-face teacher can steer discussions and other interactions in much the same way a driver can steer (or stop or slow or speed) an automobile, an online teacher gets one chance to begin discussions or interactions. By the time the need for changes in online discussions become obvious, it can be too late to make them.

Multimedia

Whereas the first generations of computers used alphanumeric input and generated similar output, recent generations of digital devices are capable of capturing, managing, and disseminating high-resolution images, audio, and video. Further, networks have improved so they can carry that information with little latency. As a result, instructors and instructional designers can use multimedia files in online courses.

Scholars have identified several aspects of multimedia that can guide course design. First, learners do pay increased attention to information that is presented in multiple media compared to information that is presented only as text, but motivation and the level of one’s cognitive engagement also affects attention.

Second, multimedia can be understood as a progression of modes, each better than the preceding. Simple text is the least effective. Text supported with graphics is better. Text and graphics presented together is better. Visual text, graphics, and an audio version of the text is better still; and a natural voice reading the text is better than computer-generated voice (Mayer, 2005).

Third, options that allow the user to control the presentation (pause, rewind, fast forward) as well as navigation aids and content cues are associated with improved attention to and memory of multimedia resources. This effect is observed when the cues and controls are well designed and do not introduce extraneous cognitive load or draw attention away from the content.

Feedback and Evaluation

The final phase of designing a good online course is deciding how students will get on their work and give feedback to others. We do know that giving feedback is a part of active and social learning that increases cognitive engagement, so it is an important aspect of the course that should not be neglected.

Some instructors (and students) can become confused when using the terms “formative assessments” and “summative assessments.” Ostensibly, formative assessments are those used to determine students’ progress, but that are not included in grades. This can cause confusion as (despite instructors’ best efforts) students cannot clearly differentiate the activities that are formative assessments from those that are summative assessments. Further, instructors often find students do not complete formative assessments as they reason, “this doesn’t count.”

To avoid the confusion and to encourage students to actively participate in using feedback, many instructors will allow multiple attempts at assignments that they want to be “formative,” but they will not use the language to thus identify the assignments. For example, instructors may allow students multiple attempts at quizzes which are more brief and more frequent than exams which are fewer and longer and that may not be done more than once.

The final phase of designing a good online course is deciding how students will get on their work and give feedback to others. We do know that giving feedback is a part of active and social learning that increases cognitive engagement, so it is an important aspect of the course that should not be neglected.

Some instructors (and students) can become confused when using the terms “formative assessments” and “summative assessments.” Ostensibly, formative assessments are those used to determine students’ progress, but that are not included in grades. This can cause confusion as (despite instructors’ best efforts) students cannot

clearly differentiate the activities that are formative assessments from those that are summative assessments. Further, instructors often find students do not complete formative assessments as they reason, “this doesn’t count.”

To avoid the confusion and to encourage students to actively participate in using feedback, many instructors will allow multiple attempts at assignments that they want to be “formative,†but they will not use the language to thus identify the assignments. For example, instructors may allow students multiple attempts at quizzes which are more brief and more frequent than exams which are fewer and longer and that may not be done more than once.

Leverage Technology

One of the advantages of using an online classroom even for sections that meet face-to-face is the availability of technology tools to help with giving feedback and evaluating students’ work. In particular, grading some work is more efficient through automation and teachers have a single online place to find files submitted by students. Also, rubrics that are built into the online course can be applied to assignments. Any learning management system will provide tools for online quizzes and tests as well as the capacity for students to upload files.

Quizzes and tests can comprise both computer-graded items (such as multiple choice, calculated questions, or hot spot questions) and questions that must be graded by the instructor. These can be immediately scored, and instructor and course designers can add feedback based on a student’s answers.

When students upload files as a submission, it is time-stamped and the original file will stay associated with the assignment for that student, so there is no doubt about what was submitted and when it was submitted.

Many instructors find the work of creating online quizzes and tests to be more time-consuming than creating the same with a word processor. While that is accurate, many find the ability to reuse questions and the ability to provided automatic grading and automatic feedback to make the time well-spent. Also, many textbook publishers will provide test banks that can be uploaded to the common LMS platforms, so the work of creating questions become work of selecting questions.

Online courses can be a strange space for students. Most are very comfortable with taking tests and quizzes on paper, and they are used to handing papers (and other media) to instructors, and most are comfortable attaching files to email messages. For convenience and security, most online instructors rely on the tools in the LMS provided by the school to manage work used to evaluate students.

To ensure students are familiar with the online interface, many instructional designers recommend instructors include a low-stakes test or submission early in the course. This provides students experience navigating the MS tools that will be used to submit assignments that affect their grades before the stress of the term and simultaneous deadlines in multiple courses cause stress.

Actionable Rubrics

Rubrics generally serve two purposes. First, they are scoring guides and help faculty evaluate students’ submissions. Second, they provide scaffolding for students to understand what comprises a good submission.

Rubrics that are written in general terms are generally not considered “actionable.” Students who review the characteristics of work defined in the rubric, but who are unable to identify gaps in his or her own work may have been given access to an actionable rubric.

In some cases, faculty are reluctant to supply too much detail in the rubric as it can allow students to rely on the rubric rather than making their own decisions about what belongs in the submission. Regardless of details provided by the rubric, it should serve as a tool for students and teachers to discuss work.

Many instructors find using the same rubric for similar assignments can help focus discussions, and similar rubrics or at least language used across departments can facilitate students’ development of increasingly sophisticated knowledge. Many instructors also find making benchmark assignments to be an effect strategy for helping students understand what the language in the rubric looks like when an assignment is complete.

Resources for Understanding Rubrics:

- Carnegie Mellon University provides this page on “Grading and Performance Rubrics.”

- The University of California- Berkely provides this page on “Rubrics”

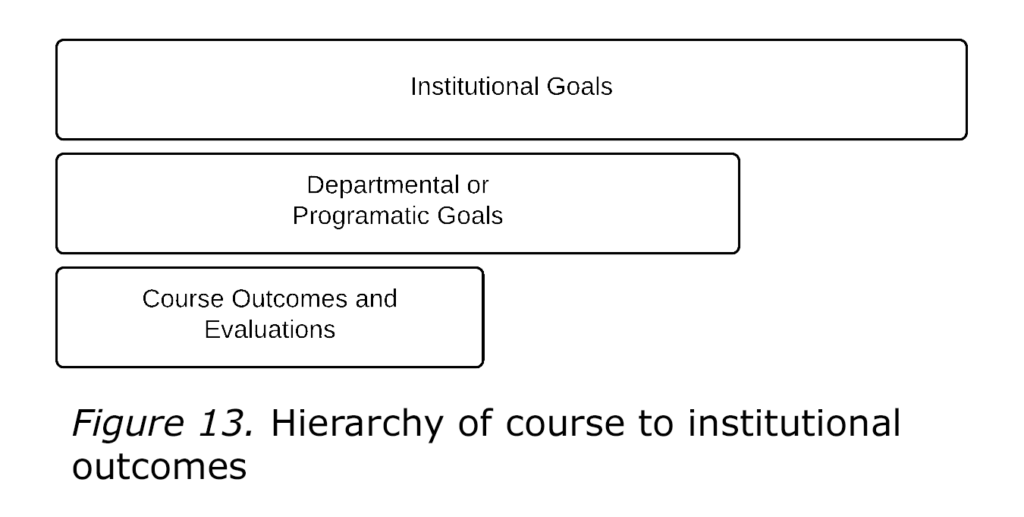

Course in Department/ Program/ Institution

A final step in defining the evaluations that are part of a good online course in to ensure the outcomes and products, as well as the evaluation strategies are aligned with those of the department or program as well as the institution.

In some cases, this will require faculty and leaders compare the course to outside standards that are published by accrediting agencies or professional organizations. This is especially true when the program is intended to prepare students for professional licensing exams.

Most institutions have also identified learning outcomes that will characterize all graduates. While these are necessarily broader than are the goals of individual courses, and the evaluations of students’ that are part of the course, there should exist a clear connection between institutional goals and the goals of each course. Course designers work with instructors to ensure each course fits into the larger goals of the department and school.

Conclusion

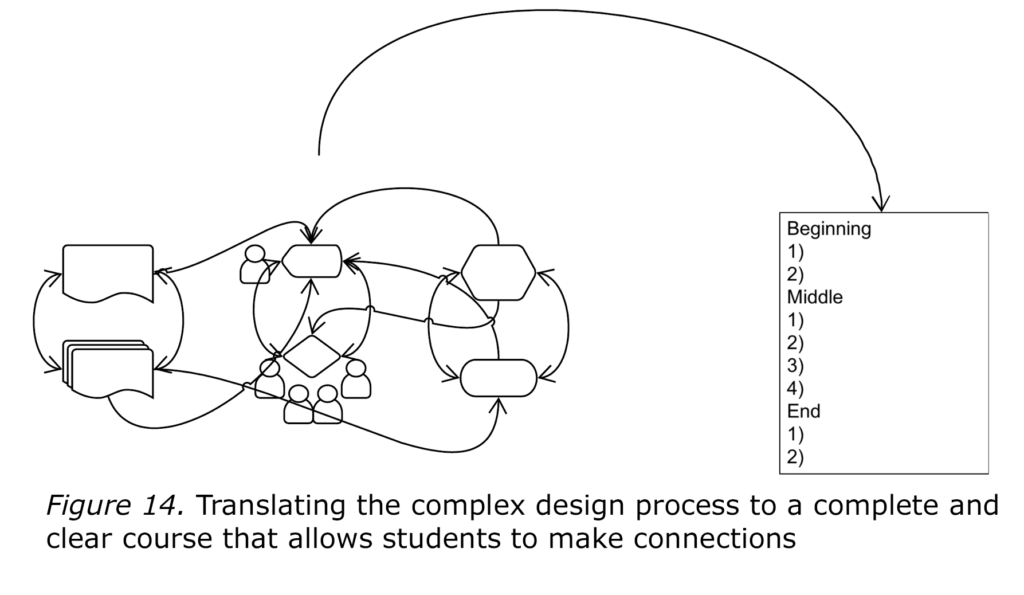

While some present online course design as a linear process (proceeding for example from analysis through design and development to implementation and ultimately evaluation- when the process begins again), it has been presented here as a series of negotiations. The negotiations are more explicitly iterative than in other models of online course design.

In reality, this is an oversimplification of the work instructors and instructional designers undertake to design complete, clear, and connecting online courses. Consider, for example, the products designed for learners to demonstrate their learning. These have implications for the strategies used to evaluate students. Also, the strategies designed to give students feedback are connected to the interactions instructors design. Further, the outcomes of the course determine the nature of the information that must be provided through the course.

Online course design becomes a very complicated process; perhaps the illustration on the left of figure x illustrates the true nature of the work. That all needs to be hidden from students in the final implementation of the course. Instructors and instructional designers must ensure:

- Students understand the nature of the course;

- Evaluation methods are clear;

- The materials are easy to navigate;

- Support systems (for technology, library, and other student services) are linked;

- The course is accessible.

References

Beynon-Davies, P. (2007). Informatics and the Inca. International Journal of Information Management 27(5): 306-318. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2007.05.003.

Beynon-Davies, P. (2009a). The ‘language’ of informatics: The nature of information systems. International Journal of Information Management 29(2): 92-103. doi:10.1016 /j.ijinfomgt.2008.11.002.

Beynon-Davies, P. (2009b). Neolithic informatics: The nature of information. International Journal of Information Management 29(1): 3-14. doi:10.1016 /j.ijinfomgt.2008.11.001.

Beynon-Davies, P. (2009c). Significant threads: The nature of data. International Journal of Information Management 29(3): 170-188. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2008.12.003.

Herrington, J. (2006). Authentic e-learning in higher education: Design principles for authentic learning environments and tasks. World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare and Higher Education. Chesapeake, VA.

Herrington, A. J. & Herrington, J. A. (2007). What is an authentic learning environment?. In L. A. Tomei (Eds.), Online and distance learning: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications (pp. 68-77). Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference.

Herrington, J., Oliver, R., & Reeves, T. (2003). Patterns of engagement in authentic online learning environments. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 19(1). doi:0.14742/ajet.1701

Mayer. R. (2005). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In The Cambridge handbook of Multimedia Learning, Richard Mayer (ed.), 31-48. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Poh, M. Z., Swenson, N. C., & Picard, R. W. (2010). A wearable sensor for unobtrusive, long-term assessment of electrodermal activity. IEEE transactions on Biomedical engineering, 57(5), 1243-1252.

Rule, A. C. (2006). The components of authentic learning. Journal of Authentic Learning 3(1), 1-10.

last updated: July 14, 2018

Dr. Gary L. Ackerman

http://www.hackscience.net