The time since COVID, I have noticed a growing trend in posts related to teaching on social media. In a nutshell: Teachers are “complaining” the students are “doing nothing.” They are getting pushback suggesting they need to make their courses more interesting and engaging.

This is certainly not a new trend—I recall both the complaints and the pushback from the earliest days of my career which started in the late 1980’s. Just like most problems, this is not as simple as either the complaining teachers or those pushing back would have it.

Effective teaching and learning require the effort of both teachers and students. The teachers must plan, design, and then deliver effective lessons. Effective lessons will engage students and result in their brains changing so that they can use the new information and skills in that class, in other classes, and in other settings. (This is not a satisfactory definition, but this post isn’t about effective teaching.) These lessons require effort from the teacher to prepare and present, and in many cases adjust what requires the least effort to what requires more effort.

Students must exert effort to learn. Actually, that is not accurate. Learning is hard work. Students must attend to the lesson, reconcile what is new with what they already know, and practice so they can remember and work to apply their new knowledge.

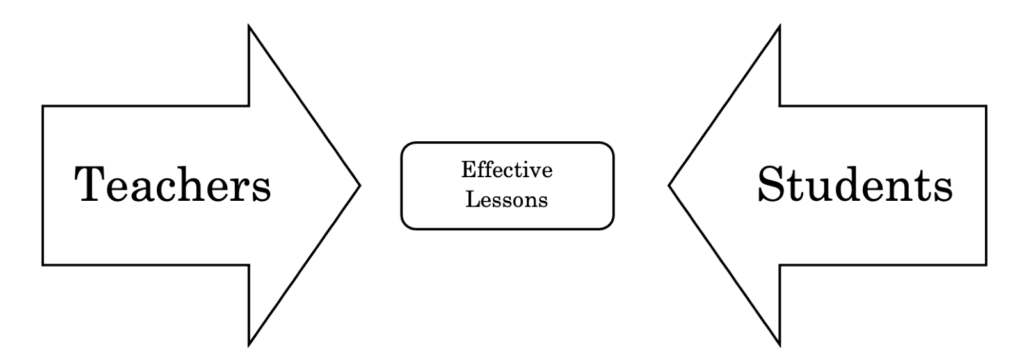

Much of the school curriculum is also built around topics and assignments that are not performed elsewhere and that neither teachers nor students would complete were they not in school. As a result, the participants in classrooms must meet in the middle; teachers must accommodate students and students must actively engage. I conceptualize the dynamics of classrooms as two arrows pointing toward each other. When teachers adjust their classrooms to appeal to students and students accept the lessons as worthy of attention, the lesson can be effective.

Teachers move towards students through the design of their lessons. For example:

- Including relevant and important topics

- Designing lessons around engaging problems

- Proving clear explanations

- Giving timely feedback

- Building relationships

Obviously, this is an incomplete list, and the adaptations are not universally effective.

Students move towards teachers by attending to the lessons. For example:

- Showing up to class

- Completing assignments (e.g. read the text, actively listen, think about the information)

- Complying with the intent of the lesson (e.g. actually write the essay rather than having AI write it)

- Avoiding distractions like cell phones

- Conducting oneself in a reasonable manner

Obviously, this also is incomplete, and the degree to which one does any of the things on this list varies due to many factors.

Problems occur in classrooms when either teachers or students (either collectively or individually) decide they are doing all they should and the other must accommodate them.

Teachers must realize the lessons they plan, even if they are aligned with “best practices” (many of which are not), are not as engaging and important as they believe. Students may not be as motivated by the subject as they teacher, they may not believe the teacher who says “this is important” but who cannot demonstrate the importance, the teacher may have unreasonable (and unjustified) classroom rules, or students may reject any other practice designed to coerce compliance in the classroom.

Students often refuse to engage in class work for as many reasons as teachers refuse to accommodate the interests and perceptions of students. There may be significant differences between the cultural expectations of their background and the background of the teacher, they may be exhausted from situations that occur outside of school, they may not see the relevance of the curriculum, or they may just be bullying the teacher.

Both teachers and students are in a situation in which the other can be blamed for ineffective lessons. Both must act to resolve the situations, but it is my opinion that teachers bear greater responsibility. We are largely in control of what happens in our classrooms. We must work to create interesting curriculum, deliver engaging curriculum, and nurture positive relationships. These are the foundations of effective classrooms, and we cannot hope for engaged students if we don’t build such classrooms first.